Modern air/fuel ratio sensors can sometimes bring a little bit of confusion as they can be hard to test.

You certainly can't test amperage with them using a lab scope. You really have to check in the scan data to see what that air/fuel ratio sensor is doing and whether or not it's actually working properly.

So let's go through a little bit of a description of how they work and then we'll go through the scanner and see how to test them.

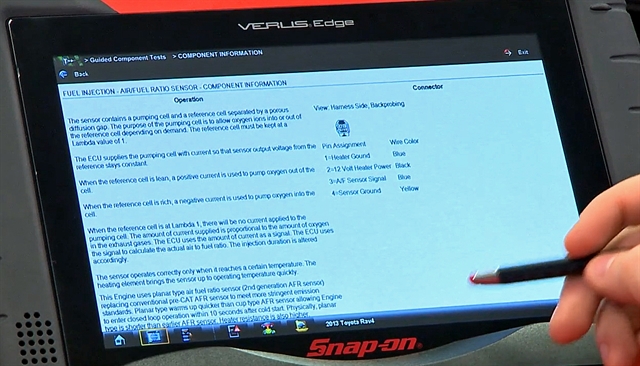

Let's get into some information about how they work first. There’s a good place for that, if you have a scan tool with Guided Component Tests.

With the tool hooked up to our vehicle, a Toyota Rav4 for this example, we'll go in to the Guided Component Tests menu, to the Fuel Injection System, and there it is – Air/Fuel Ratio Sensor.

The first thing to go to is Component Information once we open a component, so we'll go in there and see how it works.

The sensor contains a pumping cell and a reference cell separated by a porous diffusion gap. So basically it's like two oxygen sensors together in a sandwich.

The purpose of the pumping cell is to let oxygen into or out of that reference cell, depending on whether it's needed or not.

The computer is always trying to keep that reference cell at a lambda value of one or a metric which would be 14.7 to one air/fuel ratio.

So to do that, the ECU supplies the pumping cell with a current so that the sensor output voltage from the reference stays at a constant. It's trying to keep that reference voltage the same.

When the reference cell is lean, a positive current is used to put more oxygen out of the cell. When the reference cell is rich, a negative current is used to put oxygen in to the cell.

When that reference cell is at lambda one, there'll be no current applied to that pumping cell. So the amount of current supplied is proportionate to the amount of oxygen in the exhaust gases.

The sensor operates correctly only when it reaches a certain temperature, so these things get pretty hot, pretty fast.

With these newer ones it's within 10 seconds. It's hot enough to start and it's over 1,250 degrees.

Also remember, output is opposite of what you'd see with a normal oxygen or a conventional oxygen sensor.

It’s a higher voltage under lean conditions and lower voltage under rich conditions, which is the opposite of how a normal oxygen sensor would work.

It also reacts a lot faster to these AFR sensors and you're usually going to see, because the signal lines are biased with about 2.9 to 3.3 volts. So when it's just sitting there, you'll see roundabout 2.9 to 3.3 volts.

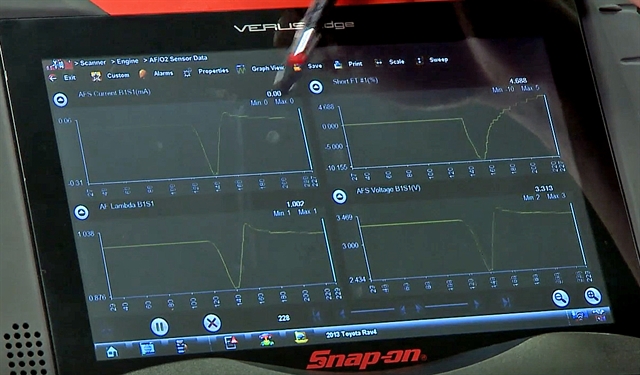

So with our tool hooked up to the vehicle, let's go into the scanner and see what data we can retrieve. Go into Engine then Data Display AF Sensor Data.

A whole bunch of data is shown but we don’t really need a lot of it so let’s pare it down using a custom data list. Hit Custom, then deselect everything, and in this instance we just need to select AF Lambda, AF Current, AF Voltage. Plus, I’d also like to see what the Short Term Fuel Trim is doing in relation to those.

Go back to the list and graph them all up if you want. You then need to start up the vehicle and see what the graphs show.

You see there's where it started up, at idle, and the computer is trying to keep that lambda back to around one.

So right now we're looking at 1.0 and notice how the current, like it said before, there's going to be no current flowing through as long as that lambda is close to one.

And we can see also the voltage is roughly round about 3.3 volts there. So it's behaving exactly as it would tell us.

So if you hit the throttle a couple of times you can see how quickly the graphs react. Three quick jumps in succession. Everything follows everything else. The short-term fuel trim reacts very quickly.

And this is the reason why these vehicles are so good with fuel economy and can adjust their fuel so quickly, by using those AF sensors.